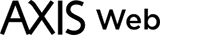

It seems to be a watershed moment for Design Education. The Dean of the School of Design at the Politecnico di Milano, Francesco Zurlo, looks ahead at the challenges awaiting humans and businesses, in a world ridden with uncertainty. In this thoughtful interview he shares with us his vision on Design – an agent of systemic change that our world so badly needs.

▲Francesco Zurlo is the Dean of the School of Design at the Politecnico di Milano and President of POLI.design, a non-profit consortium founded by the Politecnico di Milano. His research scope encompasses the strategic, systemic and creative facets of design – to unearth sustainable trajectories for innovation and human development in the business space.

ーーAs a design educator, what do you think are the most challenging aspects as we transition into new remote learning settings?

There are many answers to this question. We’ve moved into a “new normality of uncertainty” and there are a lot of challenges ahead. I think a good place to start though would be the quintessential designers’ skill, empathy. You can frame it as the ability to see how people behave in emerging and specific contexts of use. And to my view, this ability is strongly bound to a condition of spatial presence. What I mean by this is being in the same place with other people, interacting with our surroundings through our own body.

It comes down to a concept called proprioception, a kind of non-cognitive bodily self-awareness – sometimes referred to as our sixth sense. Now, proprioception plays a huge part in our understanding of the world and of our own identity, because it helps us trace the boundary between the self and the others.

Besides, research indicates that memory-building processes and spatial experience are somehow closely connected, which suggests that remote and online settings might pose some very important limits to teaching and learning.

By the time we remove our body from the physical place, we limit our chances to experience space and as a result our whole memory-building process is affected.

A case in point is the phenomenon known as Zoom Fatigue, which occurs when we get wrapped up in an absence of space. No matter how sophisticated technology becomes, virtual interactions seem unable to solve the lack of togetherness, and this is all the more relevant when it comes to learning design.

Another important implication worth mentioning is the impact that distanced education has on practice, aka learning-by-doing, which is a staple approach in design education.

For designers, doing and thinking are tightly interwoven and they coalesce around team working. By its nature working with others hinges so significantly upon our bodily presence, our movements, touch and gestures, as these are important means to communicate and build relationships in a collaborative space.

While we may temporarily play along with the idea of replacing physical interactions with virtual ones, this trend will have to be reversed, eventually. There’s a bunch of research by scholars at Palo Alto University suggesting the importance for students to attend the physical ecosystem they belong to. As far as I’m concerned, this stretches beyond their university campus to include the neighborhood, the local community, the whole city. In order to fulfill design’s true potential, I think that students should return to this “school of life”.

ーーWhat sets Design Education apart from other types of higher education?

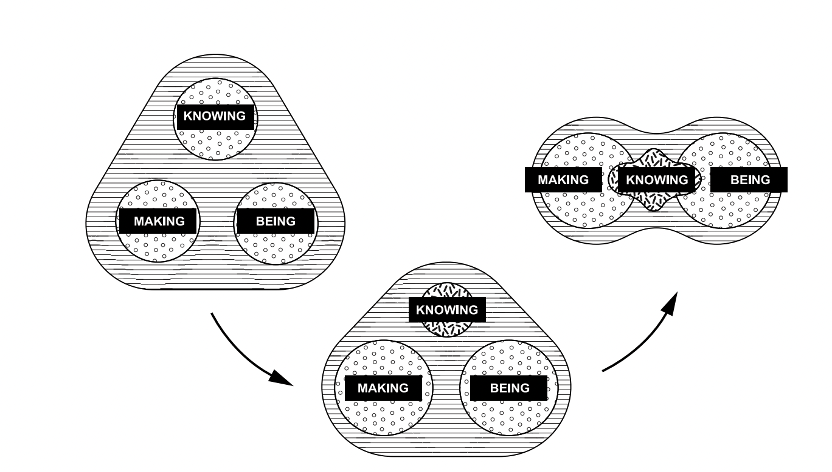

Until recently we’ve been referring to a magic interplay between being, knowing and making in the following terms. Being is all about soft skills. I’m talking about negotiation, mutual accountability, collective creative problem solving, project ownership, leadership. In a nutshell, everything you have to learn in order to work successfully with other people.

Knowing encompasses the notions that help you go about building a design career. It includes a variety of things: expertise around materials and tools, principles of visualization, sociology, psychology and so on.

This rich body of knowledge underpins making, which is when ideas turn into artifacts and tangible concepts.

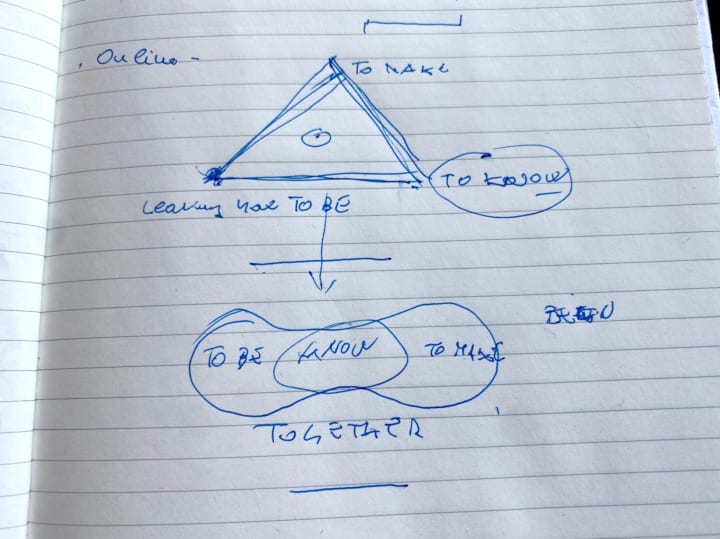

In the traditional model of design education, these three components are encapsulated in a sort of triangle-like shape, and practice follows knowledge. Today we edge towards a different approach, where knowing emerges naturally from the intersection of making and being. We visualizes this as a bean-shape framework which recalls the symbol of infinite.

▲ Model of design education is changing.

▲ Illustration by Prof. Zurlo during the interview.

This new model is a fundamental shift, as more agency is given back to students, along with a compass to create that knowledge by themselves.

Importantly, learning-by-doing is only a part of the process; the being component with all its soft skills, is crucial. Again, it connects back to that idea of togetherness.

ーーIn one of your papers you discuss the changing landscape of design education. Which role are younger generations playing in that?

Young generations are ushering in a massive change. In an ever distracting reality where their ability to focus is constantly hijacked, students have learnt how to engage with ever expanding digital networks.

A beautiful metaphor by the great French philosopher Michel Serres captures their unique way to access knowledge: ‘Thumbelina’, a honorific granted on account of the dexterity of their thumbs, as they nimbly glide over the screen of their smartphone. At its core is the now widely known pedagogical ideal of a “well-done head”, brought about by the Enlightenment – as opposed to a traditional view of education centered around more passive ways of learning.

Today this concept makes so much sense in a world awash with information: I think the role of Design Education today is not so much about filling students’ heads with notions, as it is about giving them a compass, a framework for them to be and to make in this reality – and only through these two, to build their own knowledge of it.

ーーHow about the future of design education?

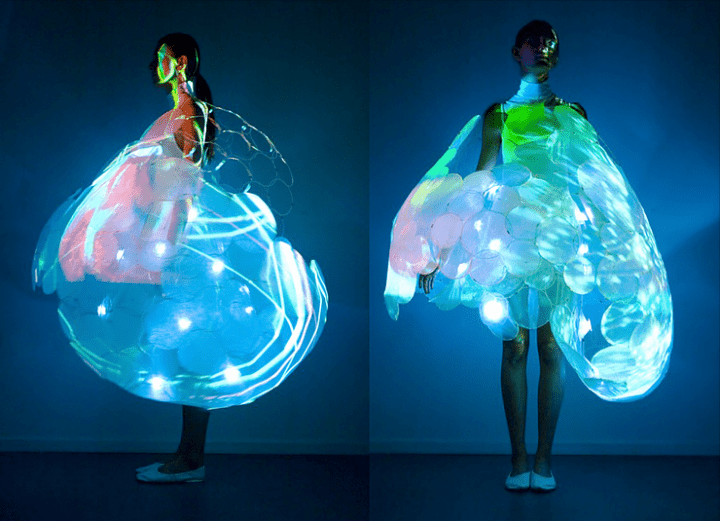

At the moment, digital transformation and the green agenda are two major forces pushing for design driven innovation, so I think design curricula will need to change accordingly.

A study conducted by Entity Design has quantified the competences required to build a so-called digital twin (i.e. a virtual model designed to accurately reflect a real, physical object). I was struck by the number – a staggering 62 specialisms!

That figure gives you an idea of how sophisticated digital ecosystems have become.

As the elusive metaverse and other pioneering technologies take shape, while complex challenges unfold on a global scale, vertical, technical specialization are becoming in high demand, but paired with an ability to integrate different specialisms.

Once companies understand this, they realize what a massive competitive advantage design can be. By its nature design works as a bridge and a connector among specialisms. We can think of it as a new Esperanto, or as a way to speak simultaneously in different languages. Crucially, such a “polyglot” ability can be decisive when it comes to tackling systemic change, particularly in the context of a circular economy.

Here another keyword worth mentioning is co-generation, which can describe the trigger of innovative ideas through the coordinated efforts of designers, businesses, academia, communities and institutions. The topic is on the top of the EU agenda thanks to the New European Bauhaus, an international initiative which deliberately draws inspiration from the influential Bauhaus movement born in the 20th century. Its vision is to encourage innovation by means of purposeful creativity, promoting a concept of “beauty” which is deeply rooted in environmental sustainability, social equality and social good – in the words of a great pioneer of social innovation, Victor Papanek, “bridging human needs, culture, and the environment”.

So I think the challenge for design in the near future boils down to this one point:

leveraging on its natural vocation to connect and orchestrate different actors, in order to co-generate purposeful solutions that bring systemic change.

ーーThe Politecnico di Milano is at the forefront of Design Education, in Italy and beyond. What is it that makes it so unique?

Probably our unique take on creativity.

There are two ways to frame creativity and I’d like to draw parallels with evolutionary biology, where a dominant theory is Charles Darwin’s famous survival of the fittest – only the strongest specimen survives. By contrast, Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck’s theory posits that evolution occurs as an adaptive response by living beings to environmental changes.

Now, translate this metaphor in the field of creativity, and what you get is, on the one hand a “trial and error” approach, quite typical fine arts, whereby numerous concepts and ideas are sketched from an initial brief, only for the best ones to be developed at a later stage. This is what I call a “darwinian” approach to creativity, basically a survival of the fittest. Another way to design is more “adaptive”: it goes about by conducting research upfront and it is only when the problem space is clearly defined that directions for design are explored. The whole point is avoiding time-consuming trial errors, by building a story first, that can inform a design solution.

This is our favorite approach at Politecnico, which we also promote through a dedicated program “Introducing metadesign”: a course for students to learn a consolidated research practice to support the design process.

Another significant difference of Italian design, compared to its Anglo-Saxon counterparts, lies in its bottom-up nature – design being put forward by a thick layer of different actors, who contribute to innovation in a spontaneous, though mostly unregulated way: citizens, SMEs, local communities, institutions and entities of any sort. This participatory kind of approach is radically divergent from the top-down vision underpinning institutions like the UK Design Council.

ーーMany people advocate a “standard” for design, to better show to businesses the potential of our process. Does this fly in the face of the Italian approach that you just described?

I believe so. There are two ways that businesses can approach design:exploitation and exploration.

Exploitation is typical of the world of management – well represented by both British and American design cultures. Such a mindset has a laser focus on metrics and therefore the idea of creating a standards sounds like an appealing one, as it’s a way to measure the output of the design process.

Exploration is more related to entrepreneurship and to the proneness to take risks. It is a mode that Italian enterprises tend to lean to, and arguably at odds with a traditional metric-driven mindset. In fact, though exploration can be a huge catalyst for disruptive innovation it is hard to calculate its impact in quantitative terms. I would argue that for design to succeed in the corporate world, practitioners really have to find the right balance between these two modes.![]()